No longer possessed by the mob

Week of Sunday June 19

Gospel Luke 8:26-39

Then they arrived at the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee. 27As he stepped out on land, a man [aner] of the city who had demons met him. For a long time he had worn [Other ancient authorities read a man of the city who had had demons for a long time met him. He wore] no clothes, and he did not live in a house but in the tombs. 28When he saw Jesus, he fell down before him and shouted at the top of his voice, ‘What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I beg you, do not torment me’— 29for Jesus had commanded the unclean spirit to come out of the man. (For many times it had seized him; he was kept under guard and bound with chains and shackles, but he would break the bonds and be driven by the demon into the wilds.) 30Jesus then asked him, ‘What is your name?’ He said, ‘Legion’; for many demons had entered him. 31They begged him not to order them to go back into the abyss.

32 Now there on the hillside a large herd of swine was feeding; and the demons begged Jesus to let them enter these. So he gave them permission. 33Then the demons came out of the man [anthropou] and entered the swine, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and was drowned.

34 When the swineherds saw what had happened, they ran off and told it in the city and in the country. 35Then people came out to see what had happened, and when they came to Jesus, they found the man [anthropon] from whom the demons had gone sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed and in his right mind. And they were afraid. 36Those who had seen it told them how the one who had been possessed by demons had been healed. 37Then all the people of the surrounding country of the Gerasenes asked Jesus to leave them; for they were seized with great fear. So he got into the boat and returned. 38The man from whom the demons had gone begged that he might be with him; but Jesus sent him away, saying, 39‘Return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you.’ So he went away, proclaiming throughout the city how much Jesus had done for him.

We will see nothing here if we insist on reading this as a literal story. Either we will reject it as ridiculous, which it is if read literally, or we will relapse to a first century view of the world, which would be a profound illness.

We need to read the story as a story of symbols. The places, the features, the geography, and the little details: these are neither incidentals nor measures of literal truth. They are the things which carry the meaning of the story.

The story begins in "the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee." John Petty translates this as "over against Galilee." Galilee is the place of the proclamation of the gospel. It is the place we live the resurrected life and meet the Christ: in the tomb in Jerusalem the women are told,

He has been raised; he is not here. Look, there is the place they laid him. 7But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him, just as he told you. (Mark 16:6-7)

Jerusalem is a city: the city is the place of Babel, the seat of empire; the people of the city beg Jesus to leave. (8:34ff) As he arrives, Jesus is met by a man [aner male] of the city, (8:26) who lunges at him. Later, as Petty points out, this man, now in his right mind, is called a "human being." [anthropon] (8:35: For Jesus had commanded the unclean spirit to come out from the human being.) And this human being sits at Jesus' feet rather than seeking to drive him away.

Petty makes another connection to what has gone before:

This kind of phrase [of the city] is reminiscent of the "woman of the city" in Luke 7:36 - 8:3. Each of them has this much in common: they were both on the fringes of society, the woman because of her "impurity," this demon-possessed man by his complete separation from others.

Mark D Davis adds to this:

In v. 34 … the herders will go “in the city” and tell about what Jesus had done. Luke is keeping the lines of communication between the city and the events at the shore or in the Pharisee’s house open.

The other connecting symbol in this part of Luke is the power of Jesus.

He has placed it as one of three stories that demonstrate Jesus' power, first over the forces of nature (8:22-25), second over the demonic world (8:26-39), and third over death (8:40-56). (John Petty)

But what is the power of Jesus in these stories? Is it different from the power of the city? I think the city stands for culture which is not the culture of Galilee; culture which is seeking to live as the incipient Kingdom of God. The power of city is adherence to the myth of redemptive violence (as outlined by Walter Wink); the idea that violence and evil can be purged by yet more violence.

Rene Girard says,

If need be, the demons will tolerate being expelled provided they are not expelled from their country. [He is referencing Mark's telling of the story at Mark 5:10] This would seem to mean that ordinary exorcisms are always only local displacements, exchanges, and substitutions which can always be produced within a structure without causing any appreciable change or compromising the continuation of the whole society. Traditional cures have a real but limited action to the degree that they only improve the condition of individual X at the expense of another individual, Y, or vice versa. In the language of demonology, this means that the demons of X have left him to take possession of Y. The healers modify certain mimetic relationships, but their little manipulations do not compromise the balance of the system, which remains unchanged. The system remains and should be defined as a system not of men (sic) only but of men and their demons.

Girard and those building upon his insights, see that in the story of the demoniac, Jesus does something completely different from a shuffling of the deck chairs or, in this case, of our demons.

So what is the change Jesus makes?

In classic scapegoating behaviour, people are stoned. They are driven out from the city. They are thrown from high places. The sins of the people are laid upon the one individual.

We have already seen this in Luke Chapter 4:

29They got up, drove him out of the town, and led him to the brow of the hill on which their town was built, so that they might hurl him off the cliff.

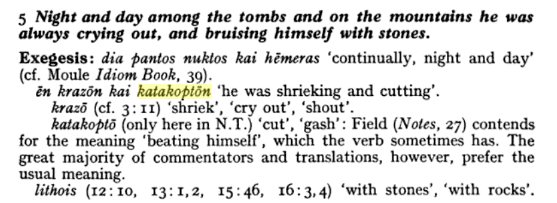

In Mark's story, the man is gashing or beating himself with stones. (Mark 5:5) He is stoning himself! He is accepting, in some way, the verdict of the mob.

In Mark's story, the man is gashing or beating himself with stones. (Mark 5:5) He is stoning himself! He is accepting, in some way, the verdict of the mob.

Hammerton Kelly says of this:

He carries his persecutors inside himself in the classic mode of the victim who internalizes his tormentors. He even mimes the lapidation by which he was driven out, compulsively belaboring himself with stones and crying his own rejection. He imitates his persecutors to the extent that he becomes his own executioner in the mode of self-estrangement characteristic of the mimetic crisis.

It makes him the living dead: He has no clothes and lives in the tombs. (Bailie)

At this point the story is grimly familiar for anyone with the least exposure to hospital mental health wards, where people self harm, and quite often insist on being naked. The correlation between those who are mentally ill and those who have suffered traumatic abuse is striking. And one particular mental illness which I have met reflects another aspect of this story. Dissociative Identity Disorder, living as Legion, also has strong correlations with abuse, and with self-harm.

Understand that to then say the man had DID is to miss the point entirely. DID might be diagnosis of a symptom, but it is no healing of a disease. The man and his city are a symbol of what is wrong— the disease— with all our cities. To say Jesus healed a man with DID, as thought that is a significant reading of the text, is to shuffle the deck chairs. It is as shallow a reading of our malaise as the psychiatrist who thinks mental illness is all down to brain chemistry gone wrong. (Although, sometimes, this is what is making a person ill.) It is to turn away from reading the symbols and to retreat into the literal. In a real sense, it is to ask Jesus to leave our city alone.

Here is Girad's reading of what Jesus does. He dismisses our concerns over the literal details and identifies something else:

The Gospels are too interested in the diverse forms of collective death to be interested in the topography of Nazareth. [There is no cliff] Their real concern is with the demon’s self-lapidation and the fall of the herd of pigs from the cliff. But in these cases it is not the scapegoat who goes over the cliff, neither is it a single victim nor a small number of victims, but a whole crowd of demons, two thousand swine possessed by demons. Normal relationships are reversed. The crowd should remain on top of the cliff and the victim fall over; instead, in this case, the crowd plunges and the victim is saved. The miracle of Gerasa reverses the universal schema of violence fundamental to all societies of the world.

When we look at the expelling of victims, there is something about the story which does not at first seem to fit the pattern, because the city tried to chain this man up, rather than kill him outright, or expel him. They needed him. This is how our culture works, still, too often. We need a scapegoat. We need a victim to set ourselves "over against."

And the victims play the game, because there is no way out. How can you step out of it? The poor being victimised by the Republicans vote Republican, listening to the lie of trickle-down economics an making America great again. Australia, most fragile land that we are, votes for the owners of the rich miners of coal who are destroying us and seeking to destroy alternative energy industries, while seeking our own scapegoats in the refugees and the Muslims.

We are sinking like the Titanic, the un-sinkable ship.

In denial of the biologically an ecologically obvious— most species that ever existed are now extinct— and in denial of the historically obvious— great empires and civilisations fall and disappear— we simply shuffle the deck chairs; the world is outraged at the death of a gorilla. "Appreciate the congrats for being right on radical Islamic terrorism, I don't want congrats, I want toughness & vigilance," Mr Trump tweets today, ignoring the obvious-to-everyone-but America issue of justice, guns, and violence.

In the story, the demons try to continue the deck chair routine. They seek to trump Jesus by calling out his name, and asking permission to enter the pigs to avoid annihilation in the abyss. But the pigs plunge into the deep waters of the lake. Significantly,

Abussos means "bottomless, immeasurable depth, the deep." It was a place for the "imprisonment and punishment of demons," says Tannehill (p. 146), who also notes that the word was used in the Septuagint to translate the Hebrew word meaning "the flood or watery deep." (Petty)

How is it that Jesus, at this point, is not using violence against violence? Hammerton Kelly says

He imitates his persecutors to the extent that he becomes his own executioner in the mode of self-estrangement characteristic of the mimetic crisis. The legion of demons is, therefore, the lynch mob….. and the demons, who are really the internalized crowd, fall victim to their own designs and tumble headlong into chaos. [I have added the emphasis]

Harking back to my posts (here and here) of last week, on being given a name, I find David Lose fills out some of the mechanism of this self-destruction:

I find it devastating that he has no name, no identity left, except for what he is captive to… He has been completely defined by what assails him, by what robs him of joy and health, by what hinders him and keeps him bound…

… Don’t we also tend to define ourselves in terms of our deficiencies and setbacks, our disappointments and failures …. enough to rob us of the abundant life God hopes that we experience and share[?] Why is it that every time we want to take a risk and in this way be vulnerable, we are reminded of every failure, every disappointment we’ve experienced before? Perhaps because we’ve allowed these things to possess us. We, too, are Legion.

Moreover, we live in a culture that seeks to create in us a palpable sense of lack. The majority of advertisements we see or listen to have as their goal creating in us a powerful sense of insecurity. Whether they focus on our looks or status, our possessions or our relationships, they try to create in us a sense of insufficiency that can only be remedied by buying the product being advertised. And all too often we comply. Not always, of course, but take a look around your home and notice for just a moment how many things you bought that you just didn’t need. Not even a little bit. Why did we buy all this stuff? Because we believed the promise the product made, but before we could believe its promise we had to believe its claim: that we are insufficient. We, too, are Legion. [I have added the emphasis]

And we, being Legion, are running toward the cliff. Our culture of rivalry "solved" by scapegoating is sinking us.

Jesus did not do violence to the pigs/crowd/mob which went over the cliff. It took itself over— could we say, it was taken over by itself? It would not and could not do without its scapegoat. This is why they ask him to leave. "This total system is threatened by the cure of the possessed and the concomitant drowning of the Legion." Girard.

Jesus says somewhere, drive out a demon and more will come in. (Matthew 12:43-45) But in this story the man sits at Jesus' feet. He allows Jesus in.

We are all "possessed." We are all, in some way, led into a fuller being by the stories told about us and the stories we try to live out. The man "the human being" listens to Jesus' story about him, and lives out Jesus' story. It allows him to be in his right mind. What mind are we in if we drive Jesus away?

What does this mean beyond mere a religious saying? Does it have content? And how does it fit in our sinking world? How do you live this practically beyond some whistling in the dark assertion that Jesus saves us (esothe) or heals us as he did the man in 8:36.

At the end of the story, Jesus sends the man back to his home. The Greek text fascinates me. Davis translates it like this:

Then the man out of whom the demons had gone to him was begging (bound?) to be with him; but he freed him saying, Go into your home, and describe that which God did for you.” And he went away to the whole city proclaiming that which Jesus did for him. [I have added the emphasis]

The word NRSV translates as sent away is

ἀπέλυσεν: 1) to set free 2) to let go, dismiss, (to detain no longer) (Davis)

The man is sent back to the place of his shame, sent back to the place where he was a victim. This frees him. He is freed by telling what God has done for him. (The text says he told everyone what Jesus had done for him: big hint!)

So as we live in a sinking world where massive species extinction is more likely than not, where the USA is rapidly sinking as the controlling empire of the world, and where climate change may mean our entire civilisation collapses, even if we as a species survive, how do we live?

We live without scapegoats. As Christians we follow the way of Jesus by refusing the violence of scapegoating. We are neighbour to all people. Having seen what the world has being doing to us, and what we have been a part of, we now, in our right minds, go back and live and tell what God has done for us. That is faith. That is our freedom.

In short, the Myth of Redemptive Violence is the story of the victory of order over chaos by means of violence. It is the ideology of conquest, the original religion of the status quo…

It is as universally present and earnestly believed today as at any time in its long and bloody history. It is the dominant myth in contemporary America [and Australia.] It enshrines the ritual practice of violence at the very heart of public life, and even those who seek to oppose its oppressive violence do so violently…

The Myth of Redemptive Violence is the simplest, laziest, most exciting, uncomplicated, irrational, and primitive depiction of evil the world has ever known… (Quoting Walter Wink at One Man's Web)

The painting: Do you see how even in the 1500s, Marx Reichlich saw the disintegration of our humanity when we attack the scapegoat? By Marx Reichlich - The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=157782

Andrew Prior

Direct Biblical quotations in this page are taken from The New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Please note that references to Wikipedia and other websites are intended to provide extra information for folk who don't have easy access to commentaries or a library. Wikipedia is never more than an introductory tool, and certainly not the last word in matters biblical!