Mark: Introducing the Crowd

This draft text covers the section of Mark from the end of Chapter 1 to Mark 2:12, including comments on crowds, and the use of the term "the Son of Man."

Introducing the crowd

The honeymoon period 1 is at an end. Until now, the religious authorities have been invisible, with only a swipe at their lack of authority (Mark 1:22,27), and an almost incidental mention as Jesus sends the man to the priest in this pericope. (Mark 1:44). But now in Chapter 2, the charge of blasphemy arises, and almost without exception, the authorities will be hostile towards him for the remainder of the gospel. (cf Mark12:28-34 for that possible exception.)

The word is now out about Jesus; he can no longer go into a town openly. (Mark 1:28, 45) People have been astounded at his actions, they have gathered at the door of houses, and even out in the wilderness places people came to him from everywhere. The crowd (as yet unannounced) has become visible in the narrative.

Across the Gospel of Mark the crowd shows the nature of humanity. Within our culture of empire the crowd is the ultimate source of authority; Pilate (cf Mark 15:15) and the Temple authorities who nominally hold the power of life and death, all bow to the crowd, even though they are often able to manipulate the crowd because they and the crowd have the same desires. They fear the crowd. (eg: Mark 12:12) Fame is bestowed by the crowd, which can as quickly focus on another, or destroy its favourite as a scapegoat. "Behind every crowd stands the original lynch mob ready to hound the scapegoat to death."2

The crowd is us. However much we seek to moderate our "mobbishness" with reasoned debate, society operates as a crowd. And this is the reason the mob finally calls for Jesus' death in Mark 15:8-15. For Jesus destabilises the crowd, and threatens its (and our) existence. True, Jesus brings hope and healing to people. But that hope is founded in his living out an understanding of reality which inevitably says the crowd itself—us—are ill-founded. Our existence is founded upon the death of the scapegoat and his healing acts are ultimately the healing of scapegoats. He contradicts our being at the most basic level. I repeat this in other words:

It is notable that Mark has not said, so far, that the onlookers have rejoiced or been delighted by Jesus. They are astounded and amazed, which we should recognise as emotions which can result in very negative responses. If the crowd were to embrace Jesus with joy and follow him, it would have to recognise this: Because it is founded in violence, it is itself the cause of the illness that he is healing. It can only be healed "by faith" (Mark 5:24b-34) which means to step out of itself, and repent. This is why the crowd is on the side of the leaders in the end, and they together crucify Jesus. The crowd is not being led by the leaders of society in this; the leaders of society are assisting the self-preservation of the crowd.3 The Gadarenes (Mark 5:17) are the early forerunner of the crowds who drive Jesus out to Golgotha. They are simply quicker to intuit what Jesus is offering, and how he is threatening their society.

In all this, the crowd knows even though it does not know. Crowds can very quickly flip into panicked violence and rage. But they— we— are not without intelligence. In its casting about for a scapegoat to blame for a hard lock-down due to a Covid-19 outbreak, my home state poured its outrage upon a hapless soul who had lied to contact tracers. No one blamed the virus. No one remembered the times that they didn't wear a mask, broke isolation orders, or had friends around for a pool party during a hard lock-down, or told their own lies to contact tracers, or voted for the successive governments that have privileged themselves and led to medi-hotel guards not having a living wage. This behaviour was common knowledge. But when people were reminded of common knowledge, they wiggled around the facts with willful blindness because it was too hard to accept that we too were "doing the very same things" (Romans 2:1) which enabled the spread of the virus. We know, and yet we don't know, and we can't. It is too hard, and too threatening, to allow ourselves to see the bigger picture of empire and how the culture of empire controls us. Or, as the colloquialism says, to recognise how empire owns us.

Because of this, we should read the amazement of the crowds much more as consternation than as a positive reception to Jesus. And where we do see the large crowd was listening to him with delight (Mark 12:37), it is the (very Australian!) resentment of the crowd towards those who have climbed to the top expressed in a delight at their chastening, rather than a delight in the gospel of Jesus.

Hamerton-Kelly makes this extraordinary statement about the healing of the man in 1:40-45: "The behaviour of the cleansed leper arouses the inquisitiveness and the acquisitiveness of the mob."4 The crowd/mob may be disinterested in a person. But it is never merely interested. Once the crowd becomes aware of an individual person, it seeks to own them. The crowd cannot co-exist with a person, it must control them. Once a person is not "lost in the crowd," or undifferentiated from the crowd, they enter the place of either victim or servant of the crowd—and such servants are always liable to become victims. The person the crowd has noticed submits to the will of the crowd or is driven from the town into the wilderness. Hamerton-Kelly says, "It does not matter if one is execrated or celebrated, the attention of the mob and the sacrificial system make it impossible for the victim to exist within the system."5 Unless, of course, they submit to it.6

We see today that celebrities are owned by the crowd of us, which very often turns upon them. The celebrity fall from grace is the scapegoat mechanism at work. We vent our rage upon our idols when they disappoint us and no longer provide us with a way to avoid our own shame. Until this moment they have provided us with an idol and aspiration, and a distraction from our selves. Their fall from grace confronts us with our own failings, but rather than face those, we pretend that the problem is all about our idol, and "cancel" them. For this reason, a celebrity is already a victim, albeit a victim postponed, because they are being used by the crowd to avoid its own pain and vacuity, and they may be further sacrificed.

When we read Mark as the story of the Messiah who is a victim, we see that (so far) Jesus comes and goes as he pleases. He is not driven out of the towns, he chooses not to remain there, and returns to the wilderness. He chooses when to return. But, for the culture and its crowds, he is always the victim, even in his moments of fame and goodwill from the crowd. Eventually the crowd will demand that he be expelled utterly; that is, crucified as the scapegoat, and then we will see that empire is ultimately powerless because even death cannot expel him from life.

A key action as followers of Jesus is to discern if we are gathered as followers of Jesus or if we have gathered as a crowd. (cf Mark 3:31-34)

The shape of things to come

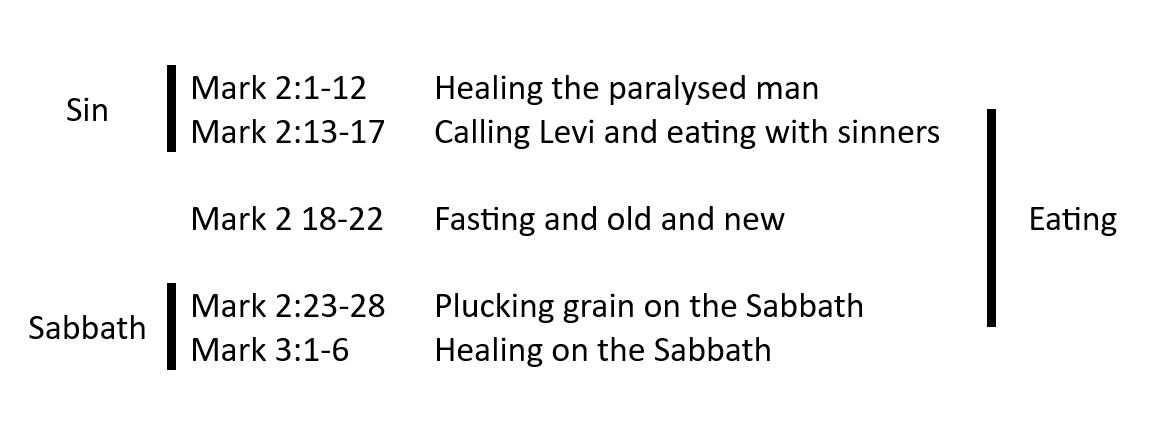

Chapter 2 begins a period of controversy between Jesus and the religious authorities which ends with their decision to kill Jesus at Mark 3:6.7 Mark has shaped this section into five controversies whose subject matter is arranged and crafted to make the point that there can be no mixing of the old and the new. Jesus explicitly says this in 2:21-22 when talking about the unshrunk and old cloth, and new and old wine skins. The arrangement of the controversies reinforces that central point. 8

Marcus9

Mark 2:1-12

1When he returned to Capernaum after some days, it was reported that he was at home. 2So many gathered around that there was no longer room for them, not even in front of the door; and he was speaking the word to them. 3Then [they] some people came [come], bringing to him a paralysed man, carried by four of them. 4And when they could not bring him to Jesus because of the crowd, they removed the roof above him; and after having dug through it, they let down the mat on which the paralysed man lay. 5When Jesus saw their faith, he said [says] to the paralysed man, 'Son, your sins are forgiven.'

6Now some of the scribes [scholars] were sitting there, questioning in their hearts, 7'Why does this fellow speak in this way? It is blasphemy! Who can forgive sins but God alone?' 8At once Jesus perceived in his spirit that they were discussing these questions among themselves; and he said to them, 'Why do you raise such questions in your hearts? 9Which is easier, to say to a paralysed man, "Your sins are forgiven", or to say, "Stand up and take your mat and walk"? 10But so that you may know that ho huios tou anthropou has authority on earth to forgive sins'—he said to the paralysed man—

11'I say to you, stand up, take your mat and go to your home.' 12And he stood up, and immediately took the mat and went out before all of them; so that they were all amazed and glorified God, saying, 'We have never seen anything like this!'

1Καὶ εἰσελθὼν πάλιν εἰς Καφαρναοὺμ δι’ ἡμερῶν ἠκούσθη ὅτι ἐν οἴκῳ ἐστίν. 2καὶ συνήχθησαν πολλοὶ ὥστε μηκέτι χωρεῖν μηδὲ τὰ πρὸς τὴν θύραν, καὶ ἐλάλει αὐτοῖς τὸν λόγον. 3Καὶ ἔρχονται φέροντες πρὸς αὐτὸν παραλυτικὸν αἰρόμενον ὑπὸ τεσσάρων. 4καὶ μὴ δυνάμενοι προσενέγκαι αὐτῷ διὰ τὸν ὄχλον ἀπεστέγασαν τὴν στέγην ὅπου ἦν, καὶ ἐξορύξαντες χαλῶσιν τὸν κράβαττον ὅπου ὁ παραλυτικὸς κατέκειτο. 5καὶ ἰδὼν ὁ Ἰησοῦς τὴν πίστιν αὐτῶν λέγει τῷ παραλυτικῷ· τέκνον, ἀφίενταί σου αἱ ἁμαρτίαι. 6Ἦσαν δέ τινες τῶν γραμματέων ἐκεῖ καθήμενοι καὶ διαλογιζόμενοι ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις αὐτῶν· 7τί οὗτος οὕτως λαλεῖ; βλασφημεῖ· τίς δύναται ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας εἰ μὴ εἷς ὁ θεός; 8καὶ εὐθὺς ἐπιγνοὺς ὁ Ἰησοῦς τῷ πνεύματι αὐτοῦ ὅτι οὕτως διαλογίζονται ἐν ἑαυτοῖς λέγει αὐτοῖς· τί ταῦτα διαλογίζεσθε ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις ὑμῶν; 9τί ἐστιν εὐκοπώτερον, εἰπεῖν τῷ παραλυτικῷ· ἀφίενταί σου αἱ ἁμαρτίαι, ἢ εἰπεῖν· ἔγειρε καὶ ἆρον τὸν κράβαττόν σου καὶ περιπάτει; 10ἵνα δὲ εἰδῆτε ὅτι ἐξουσίαν ἔχει ὁ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἀφιέναι ἁμαρτίας ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς – λέγει τῷ παραλυτικῷ· 11σοὶ λέγω, ἔγειρε ἆρον τὸν κράβαττόν σου καὶ ὕπαγε εἰς τὸν οἶκόν σου. 12καὶ ἠγέρθη καὶ εὐθὺς ἄρας τὸν κράβαττον ἐξῆλθεν ἔμπροσθεν πάντων, ὥστε ἐξίστασθαι πάντας καὶ δοξάζειν τὸν θεὸν λέγοντας ὅτι οὕτως οὐδέποτε εἴδομεν.

Translation Notes

the paralysed man (vv 3, 4, 5, 10) Note also vv 9, a paralysed man. The Greek is paralutikos and is often translated as the paralytic. They are a person, hence my use of the/a paralysed man.

ho huios tou anthropou (vv12) Mark's unannounced "dropping in"10 to the text of ho huios tou anthropou may not, in fact, be because everyone knew what the term meant11 —even if they thought they did! Its multivalent meaning may have been as enigmatic then as it is now. In this way thinking, the Gospel of Mark is challenging us to answer the question, "Who is this Jesus ho huios tou anthropou?" for in our answer we will find the shape of our salvation despite all the terrors and traumas of the world in which we find ourselves. In ho huios tou anthropou we will come to understand and know "the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One"12 for he is ho huios tou anthropou.

How then do we translate ho huios tou anthropou? There are at least six biblical uses of the phrase which inform its meaning.

- In Hebrew, ben adam can mean an insignificant human being. In Job 25, Bildad the Shuhite asks how a mortal can be righteous before God, given that they are a ben adam who is a maggot?

- But ben adam is also only a little lower than God, as we see in Psalm 8:4-8.

- Ben adam is also an apocalyptic figure. Daniel 7:13 (quoted by Jesus at Mark 14:62, speaks of one like a ben adam coming with the clouds of heaven…

Already in these examples, adam, created male and female,13 is gendered even though the word properly means all people and not just the sons.14

The New Testament adds further layers of meaning to ho huios tou anthropou.

- It also refers to the heavenly figure who is to come. Mark 14: 61-64 directly quotes the Daniel 7 passage and identifies Jesus as this figure. We can expect that Jesus and Mark add their own interpretation to Daniel's imagery.

- Two usages of the term in Mark highlight Jesus' authority on earth. One is the present passage in Mark 2:1-12. The other is with respect to the lordship of ho huios tou anthropou over the Sabbath in 2:23-28.

- A sixth usage of the term may be as a reference to the one who will suffer, die and rise. In Mark, we see this in passages such as 8:31, 9:31, 10:33, 45.

In English, the traditional translation of Son of Man has been well described as "doubly gendered," for its use of son and man. Faced with this criticism, men are likely to point out that if we translate ho huios tou anthropou as, for example, the Human One, we lose the important word play that links Jesus' identity as Son to the Trinity.15 It also loses the connection to the cultural phenomenon where in many cases the only way a king could be in direct contact with his subjects was through his chosen son. If you were in the presence of the son, then you were in the presence and authority of the father. John's gospel makes this very point in John 14:8-9.

8Philip said to him, ‘Lord, show us the Father, and we will be satisfied.’ 9Jesus said to him, ‘Have I been with you all this time, Philip, and you still do not know me? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father… (NRSV)

This is still a cultural phenomenon; witness the people lined up from 4 a.m. to welcome even the grandson of the Queen to our suburb, as he arrived on the brand-new bitumen laid only the day before!

It is important not to lose these connections which are clear in the Greek text. (Although I cannot see that the Greek text is not itself already gendered.) But… I was assigned as male at birth, and although uncomfortable with that designation, have benefited from, and been shaped by, the privileges that this brings, often unconsciously. This is despite since childhood having been aware of the violence which diminished the being of my mother and sisters—an awareness especially heightened as my wife and I sought to navigate the sexism of the church as candidates for ordination. I was ejected from college for a year because the faculty thought I was more concerned about my wife's preparation for ministry than my own, an hypocrisy which still rankles; I was fervent about this issue. The point I wish to make is, that despite all my use of inclusive language and un-gendered hymns, and frequent pro-feminist sermons, I have had little idea just how gendered and male-normative the church and its theology is.

I have realised this because, in more recent times, the mostly suppressed issue of my own gender status has refused to be ignored. And "when you see… you see." A raft of issues became newly real, grief filled, and barged into my everyday life and relationships. And this non-binary person has begun to find male hetero-normative language, behaviour, and violence, painful and frightening in a way they had never imagined. Son of Man is not doubly gendered, but triply so. To think Son of Man is an adequate or just translation is to ignore half the world. And Sons and daughters of Adam and Eve!? Who, and where, am I in that?

In my long conversation with Mark, I have struggled with the translation of ἡ βασιλεία τοῦ θεοῦ, finally settling upon "the culture and way (Basileia) of God" as a translation. (See Mark 1:14-15 Jesus begins his ministry: Translation Notes) In a similar fashion, I am inclined to leave ho huios tou anthropou in the text just as it is, as a term which will confront us and with which we must come to terms on each of its 14 appearances. Who… what... is this Jesus ho huios tou anthropou?" In our answer to this question when ho huios tou anthropou drops into the text, we will find the shape of our salvation despite all the terrors and traumas of the world in which we find ourselves.

Must my congregation learn Greek? Only if they wish. In preaching I would use the most appropriate wording for ho huios tou anthropou that suits the context, whilst alerting people to the "one dimensionality" of that translation relative to the Greek text.

Healing and Faith

This story of healing is a Markan Sandwich because the story of the man brought by his friends and healed by Jesus, is interrupted by the story of the scribes. The sandwich is skillfully made; it looks "all of one piece," but the scribes who are deftly inserted into it are used to highlight the meaning of faith and faithlessness. Although the man is healed, the scribes "can understand neither what Jesus is doing nor what he is talking about."16 They remain stuck in their current understanding of reality; we could again use the word paralysed. There is an unspoken but undeniable contrast drawn by the story: the demons themselves know who Jesus is, (Mark 1:24,34) but the scribes are blind to who he is.

The story is about the healing of paralysis—the man is referred to as paralutikos four times.17 Being paralutikos defines everything about him; he has no agency of his own; he must be carried. Jesus responds to the faith of the friends, but the man also shows faith in Jesus by standing up and walking. Faith involves action, and at the root of the act of faith is a trust that Jesus can heal us. If we will not trust him, then we risk remaining paralysed just as the man, in his hopelessness could have refused to stand and walk. And we, too, will be carried—swept along—by whichever crowd is around us.

But… there is a serious pastoral issue in this story of healing. Then, as now, some folk would have been skeptical of the actual physical healing of the man, whilst taking the spiritual lesson of the healing of paralysis in our lives. But few would imagine that the healing of the paralysed man was restricted to the biomedical organic physical healing of that person. Yet that is exactly what we imply if someone for whom we pray is not physically healed, and we then accuse them of a lack of faith. Healing is far greater and wider than mere biomedical remediation, as profound and joyous as that can be. In this case, Jesus sends the man home (eis ton oikon sou.) The man is restored to his place in society, as well as being physically healed.

What are we doing if we say someone lacked the faith to be healed? We are deflecting our fear of death—if God did not heal this person, God might not heal me, and I might die— We deflect this fear by expelling (from the house) the (in our mind) unhealed person. We are making them our scapegoat, so that our congregation will not be fractured by fear, and this happens far too often.

The Crowded House

As at the sea, (Mark 3:7) so many are gathered at the beginning of Chapter 2 that there is not room. The crowds are growing. The house is so crowded that people could not even see through the doorway from outside.18 The obvious observation that the crowd is getting in the way of the sick man has particular significance in Mark, where stepping out of the crowd and coming to Jesus is a sign of faith, and is necessary for following him, that is, model ourselves upon him, so that we begin to be healed and begin to live in the new culture he calls the kingdom of God.

Faith is Stepping Out of the Crowd

Social stability is based upon a certain unanimity and silence about the underlying violence of that which we have made sacred. That stability is shaken when someone insists on saying Invasion Day instead of Australia Day, or similar. In such a statement, we are confronted with our violence and our sacred foundations are threatened. Breaking the silence (in word or deed) and telling the truth Jesus has showed us is to step out of the crowd. For Mark, this is to show faith in Jesus.19 But faith not only steps out of the crowd, it makes us visible. And so we risk becoming a victim of the crowd.20

When we step out of the crowd we actively, practically, and visibly, reinterpret the circumstances in which God has placed us. We choose a direction other than that of the crowd. A euangelion which calls us to such an active reinterpretation of our situation is "radically noncoercive." This phrase from Hamerton-Kelly is extraordinarily important. It means that God "does not tear the covers away from mythology but…does invite one to lift the veil for oneself."21 It is not only that we cannot fathom or imagine the nature of God, but also that if God were to impose this upon us, it would itself be an act of destabilising violence. The crowd dictates. Jesus invites. And our theology should reflect that invitational nature.

What is the Blindness of the Scribes?

We cannot afford to ignore the quality of the blindness of the scribes. As is so often the case, Mark's critique of Jesus' opponents questions us: Is this me? Am I blind?

The word dialogízomenoi (questioned) occurs three times in this pericope. It has the "connotation of calculation and is almost always used in a negative sense in the NT."22 In the current text, the scribes' negative calculating dialogue is in their hearts, which means that at the very heart of their being they are failing to see or understand the full import of what is being done by Jesus.

In contrast to the scribes, Jesus perceived in his spirit what they were thinking. At one level, to perceive something in one's heart or in one's spirit is essentially the same thing.23 In each case, the seat of emotions and being is arriving at an understanding. But the heart was sometimes seen as liable to corruption,24 whereas the spirit "because of its association with the breath of God... usually has a more positive nuance."25 The phrase "in his spirit" subtly distinguishes Jesus from the scribes and shows his deep insight into human reactions while emphasising their blindness.

But the scribes are not as blind as we may first think. When it comes to the authority to forgive sins they are correct about the tradition: God is the one who forgives. Generally,26 a priest was seen to intercede with God on behalf of a person. In this case, when Jesus says your sins are forgiven he is speaking in the divine passive which indicates this intercession or brokering. Until this moment, and including when he says the sins of the man are forgiven, Jesus has acted exactly as Malina and Rohrbaugh suggest:

Nowhere in the Gospels does Jesus say, "I forgive you." Instead, as in 2:5, Mark is careful to show that God does the forgiving and that Jesus is acting as a broker on behalf of the forgiving Patron. Patrons were often absent and designated brokers to distribute favors on their behalf. What is being questioned in the challenge to Jesus, then, and what he demonstrates in his careful response, is his authorization to act as God's designated broker.27

But, if Jesus is a designated broker of God's forgiveness, then the monopoly of the current brokers is under threat. The scribes and other religious authorities see this very clearly; no blindness there! Yet it is not simply a refusal "to share power," that we are talking about here. If a human being does not merely intercede with God on behalf of another, but can forgive on their own authority, the whole cultural system will be undermined. It is not the healing itself which bothers the scribes. It is that this undeniable healing power is used by Jesus, who calls himself at this moment ho huios tou anthropou, to claim he does have authority to forgive sins.

The Crowd is Amazed

When he makes this claim and demonstrates its truth by healing the paralysed man, the crowd is "all amazed", (Mark 2:12) for the man who was paralysed, stuck, and unable to move, can now move and live freely. It is important to see that this is not a response of faith. Black [ Black, Mark, in the section on Mark 2:2-12] says Mark was "careful" to end the pericope with the crowd "left wondering." They glorify God because of the wonder of the event, not because of Jesus' relationship with God, and his possession of God's authority; in other words, they do not see who ho huios tou anthropou is.

Indeed, Hamerton-Kelly points out28 that the word translated as amazed is existasthai, and we can see a family connection to our word ecstasy. The crowd is at flashpoint because its intelligence recognises it is in the presence of something... altering. It instinctively understands it has met an alterity, an "otherness," which can change everything.

A crowd in this state is a dangerous crowd for those whose skill is to manipulate the crowd and suggest a scapegoat in order to enable and preserve their own power and security. Despite the intelligence which recognises an alterity which may be healing and freeing, the crowd is also ecstatic; that is out of its mind. Crowds which are out of their mind instinctively seek a scapegoat to restore sanity and calm; in other words, to burn off the emotional overload, as it were, and restore the safety of the status quo. Those who are the designated leaders are very vulnerable at such moments, because they are already differentiated from the crowd and highly visible, which makes them a likely target if the mob panics.

By the time we reach Mark 3:6, the religious authorities will have decided to destroy Jesus, but this decision begins here, for with his claim to be ho huios tou anthropou Jesus is not merely competing with them. He is claiming that they are no longer relevant. Ho huios tou anthropou, as we shall see, turns the religious system on its head and the authorities intuit that they could well be victims of the panic which will follow.

Mark will make much of people's ability to see or not see, particularly at 4:10-12, but also in the stories of healing from blindness (8:18-28 and 10:46-52) which bookend the teaching in between. There is an irony to the metaphor of blindness which is quite evident in the current pericope. As I have said, the scribes see exactly what Jesus is doing. They can see that he is destroying the system to which they have given their lives. What they cannot see is that this destruction is freedom, because they have not given their lives to God, despite all their best efforts. But enslaved by a system which always destroys people, and which must destroy people in order to survive, they cannot see.

There is one more thing to say about the crowd and its manipulators here. Hamerton-Kelly says29 the crowd in 3:21 is exestē which NRSV translates as out of its mind. When we read 3:21, exestē is, in fact, being said of Jesus! But Hamerton-Kelly has not misread the text; he has seen that the crowd, so much a crowd that Jesus and the disciples cannot eat, is out of its mind. The phrasing for people were saying, "He has gone out of his mind (exestē)" shows us the scapegoating has begun; the fear and vulnerability of the crowd is already being tipped onto Jesus, even if at this moment we tend to see him more as a celebrity than a victim, and do not see that a celebrity is merely a victim postponed. (cf 1:40-45 The crowd) The other way to put this is to say that the guilt assigned to the scapegoat is the guilt the crowd knows at an unconscious level is its own guilt, but cannot bear to face. What the crowd says about Jesus is, in fact, the truth about itself.

The "Son of Man" and Judgement

Mark announces "Jesus the Messiah, the Son of God," the voice from heaven announces that Jesus is "my Son, the Beloved," and the demons alert us to the "holy one of God." But ho huios tou anthropou appears unannounced and unexplained. Who is this? It is Jesus' chosen self-reference, and occurs 14 times in Mark. This is a deliberate choice by Mark30 ; Jesus could simply say "I..." What does Mark wish to tell us with this Title? Marcus suggests the way the title appears suggests its meaning was clear to Mark's audience, noting that its meaning is not at all clear to us.31

As noted, the Hebrew term ben adam was a way of saying a human one. In Ezekiel, for example, the prophet is addressed by God as ben adam 93 times.

Did Jesus mean to say that a human being has authority on earth to forgive sins?32 No wonder the scribes were offended if that is what they heard him say!

But ho huios tou anthropou does not only mean a human being in Mark. This is because in the trial where the meaning of Jesus is being laid out in full, it says:

Again the high priest asked him, 'Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?' 62Jesus said, 'I am; and

"you will see ton huion tou anthropou

seated at the right hand of the Power",

and "coming with the clouds of heaven." '33 (NRSV)

The Blessed One is a circumlocution to avoid saying God. The high priest was effectively asking, "Are you the Messiah the Son of God,"34 and in his reply, Jesus conflates this identity with ho huios tou anthropou.

The context of Daniel 7 is one of judgement, so Jesus' use of the title ho huios tou anthropou changes the healing of the paralysed man from an argument only about forgiveness to something more eschatological. But in this first appearance of ho huios tou anthropou in Mark, Jesus is a forgiver of sins rather than one coming to pass judgement upon sinners.35 Despite this, in this Markan sandwich about healing, judgement remains at the centre of the pericope because the healing of the paralysed man is interrupted by some scribes, whose calculating hearts beget a negative judgement of Jesus. Understanding the sandwich as a rhetorical form where the "filling," or the interruption, provides an interpretive condiment (as it were,) enables us to see that this is a judgement flavoured sandwich. But what we find is that judgement is a human artefact.36 God (through ho huios tou anthropou) forgives and heals and we—and the culture of empire—judge. Judgement is not laid upon us by God. We judge ourselves by the free response we make to Jesus.37 This means that when we judge others, even though we may claim to represent the truth of God, we judge themselves.

The scribes accuse Jesus of blasphemy. To blaspheme is to disrespect what God, or God's actions; in this case, they say Jesus' forgiveness of sins is blasphemous. The scribes do not recognise the presence of God in what Jesus is doing when even the evil spirits can see what is happening! Later, as hostility towards Jesus grows, he will say

'Truly I tell you, people will be forgiven for their sins and whatever blasphemies they utter; 29but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit can never have forgiveness, but is guilty of an eternal sin'— 30for they had said, 'He has an unclean spirit.' (Mark 3:28-30)

If we refuse Mark's invitation to an active reinterpretation of our situation, and of the nature of Jesus, which is mentioned above, (See above under: Faith is Stepping Out of the Crowd) then we lock ourselves into our current understanding. We refuse healing. We will become the blasphemer and impose a judgement upon ourselves, refusing the forgiveness of God.

A Hint of Resurrection

The word for standing up (ēgerthē vv12) is passive: he was raised up. The same word is used in Romans 6:4: "just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father…" Translating verse 12 as he stood up is an entirely appropriate contextual translation of ēgerthē: The man, freed of the paralysis of his being, chose to stand up "on his own." But ēgerthē is the same word as that in which Peter's mother-in-law was clearly lifted up (ēgeiren) by Jesus. (Mark 1:29) Mark quietly drops a symbol of resurrection into the text. Here in Mark 2:12, Jesus not only heals, but raises us up to freedom so that we may enter into a new culture, and a new way of being.

Andrea Prior (January 2025)

1. Marcus, pp177

2. Hamerton-Kelly, pp21-23.

3. In an effort to combat antisemitic tendencies within Christianity, some have blamed only upon the leadership, or even the Romans for Jesus' death. It is the crowd. But there is still no basis for antisemitism here; the crowd is all of us.

4. Hamerton-Kelly, pp77

5. Ibid

6. We perhaps see this in Mark 5:5 where the man was stoning himself.

7. Mark 3:6 "The Pharisees went out and immediately conspired with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him. "

8. See, for example, Marcus, pp214, based on the work of Joanna Dewey.

9. Image after Marcus, pp214

10. See the section titled The "Son of Man" and Judgement, below.

11. So Marcus, pp528

12. Cf Mark 14:61

13. Cf Genesis 1:26-7

14. Son of Adam still defines a person by masculinity..

15. In the Trinity we see the whole conception of the Godhead imagined and perceived in masculine imagery.

16. Black, Mark, section: Jesus authority resisted by authorities (1:16–3:6)

17. Three repetitions is rhetorical emphasis, four is thumping the table :)

18. cf Marcus pp215

19. Hamerton-Kelly, pp90-91

20. cf Nuechterlein, "Proper 7B" https://girardianlectionary.net/reflections/year-b/proper_7b/ Accessed 19/12/2024

21. Hamerton-Kelly, pp90-91

22. Marcus, pp216. Marcus directs us to its use in the hostility of the leaders in 11:31 (They argued with one another...) and to its use by the disciples in 8:16-17 where they do not understand about bread, and in 9:33 where Jesus asks them what they had been discussing, which was who of them was the greatest.

23. Cf the parallelism, or hendiadys, of Psalm 77:6

24. Marcus, pp216. He points us to Genesis 6:5, 8:22, and Jeremiah 17:9, as examples.

25. Marcus, pp217

26. See Marcus, pp217. Although there is a Qumran fragment which may imply that in Jesus' time "some Palestinian Jews thought that a human being on earth could remit sins for God."

27. Malina and Rohrbaugh, Social Science, "Commentary on Mk 2:9"

28. Hamerton-Kelly, pp78

29. Ibid

30. Perhaps not least because Jesus actually used the title of himself.

31. Marcus pp528

32. Cf Matthew 18:15-18

33. The reference is to Daniel 7:13— Jesus also refers to Daniel 7 in Chapter 13:26, and alludes to it in 8:38.

34. Cf Marcus pp1004

35. Marcus, pp22

36. I owe this insight to James Alison in multiple places.

37. Hamerton-Kelly p78