The Affect of Jesus

|

John 2 23 When he was in Jerusalem during the Passover festival, many believed in his name because they saw the signs that he was doing. 24But Jesus on his part would not entrust himself to them, because he knew all people25and needed no one to testify about anyone; for he himself knew what was in everyone. |

Matthew 21 14 The blind and the lame came to him in the temple, and he cured them. 15But when the chief priests and the scribes saw the amazing things that he did, and heard* the children crying out in the temple, ‘Hosanna to the Son of David’, they became angry 16and said to him, ‘Do you hear what these are saying?’ Jesus said to them, ‘Yes; have you never read, |

I'm living through one of the long downturns of my emotional life cycle. My affect is somewhere between blunted and flat. I understand some of the reasons for this: the hypervigilance of childhood trauma and all its side effects, never really stops. It is always a matter of management. Such management is not easy, because when we're down, our resistance to society's discomfort with us, is lowered. We are told we are the ones with the problem. We won't fit in; we won't lighten up; we won't get over it. It's not a fair assessment. In fact, it's the self defence of a relentlessly upbeat culture which is terrified of feeling, and especially of allowing feelings which are not positive. A person who is sad for more than a few hours confronts society with its deepest fears. Even death is allowed only a few days of being down, and then folk begin to think we should be over it, and may even tell us so.

But always I end up blaming myself. Why can I never fit in? Why am I so useless that simple life tasks are often beyond me, and always a burden? It occurs to me, as we consider our faith during Lent, to wonder just how Jesus affects all this.

Look at what he does in John Chapter 2: Jesus' storming of the temple is dragged right back to the beginning of John's gospel. In the other three gospels, his actions in the temple are the last straw in getting him arrested. In John, his driving all of them out of the temple, and turning over the tables and tipping out their money, sets the scene for reading the gospel. It is the action by which were are meant to interpret who he is, and what he means.

In Jesus' culture, the temple is God's house, literally. It is where God lives. Karoline Lewis points out a small but significant difference between, say, Matthew and John. In Matthew Jesus complains that the traders are making "my father's house" a den of robbers. In John he does not merely order them to be fair and just, but says, "Take these things out of here." It is a subtle difference, but important.

Instead of a concern for temple malpractices (“den of robbers”), Jesus orders that his Father’s house not be made a marketplace. For the temple system to survive, however, the ordered transactions of a marketplace were essential. The temple had to function as a place of exchange for maintaining and supporting the sacrificial structures. Jesus is not quibbling about maleficence or mismanagement but calls for a complete dismantling of the entire system. Underneath this critique lies also the intimation that the temple itself is not necessary. At the center of such theological statements is the fundamental question of God’s location, which will be confirmed in the dialogue between Jesus and the Jewish authorities.

Lewis outlines the way the temple authorities, in their discussion with Jesus about the tearing down of the temple and rebuilding it in three days, take the whole discussion literally. But there is something beyond the literal here, which will be typical of all John's gospel. In essence, she concludes,

If the temple symbolizes the location and presence of God, Jesus is essentially saying to the Jewish leaders that he is the presence of God. Where one looks for God, expects to find God, imagines God to be are all at stake for the Gospel of John. In Jesus, God is right here, right in front of you. That Jesus is the revelation of God, the one and only God (John 1:18), will be repeatedly reinforced with different sets of images, different characters, different directives, all pointing back to this essential truth. (Ibid)

So, the first reading of this text is that the temple is not God's house, the place where God lives, but that Jesus is the place where God lives.

We often call this "spiritualising" the text. We see a metaphor, a symbol, rather than a thing or a fact. And here we have a problem. Our culture splits the "spiritual" and the "literal" into two categories, as though one can have a literal fact, like a table, and then, perhaps, somehow have a separate godly or religious meaning of that table. In our everyday lives, this "spiritual" meaning is conveniently disconnected from the literal fact of the table, although more formally, we know there are no un-interpreted facts.

Our wider culture dismisses the spiritual meaning as irrelevant and mostly imaginary. There is no spiritual. There are only things. In the church, we cling to the spiritual as a means of comfort, but maintain the separation of the two, because to make things whole— and to be made whole— is often just too painful.

An example: A table is a table; fact. But a table is also the place where people are accepted or rejected, the place where God's love for all people is lived out. It is a symbol of hospitality, a partaking of the kingdom of God, and a living out of the kingdom of God. A table is the place where the community of divine love becomes real, or not. A table is a symbol for all that is right, and for all that is wrong with our humanity. And yet, in the churches, we have a term: a closed table. This utter contradiction shows how painful it is to live within an wholistic, connected spirituality.

Stan Duncan says of Jesus' actions in the temple that it

isn't easy to get a hold of [what Jesus is doing], given our penchant for meek and mild images of Jesus, and that’s probably why most of us (okay, maybe some of us) try to just talk about its “spiritual” side (purifying the religion of the day) instead of its more gritty, political, and economic underbelly.

That "gritty… underbelly" is the true meaning of spiritual. For spiritual is the meaning of something in the light of Jesus. And it is not just meaning as some free standing fact. Spiritual meaning implies some sort of transformative action; the spiritual is a challenge to the way we are now, a calling to become more fully human, a calling to consider what actions and events mean, and how they require us to change.

So we look at what is going on behind the event in the temple. I quote at length from Stan's article:

Jesus doesn’t appear interested in cleaning up the market system that operated at the Temple, but in doing away with its idolatrous economic infrastructure altogether…

[In the temple the] sellers sold things like cattle, sheep, and doves for the offerings, and the changers changed money from international currency to local currency. Both were corrupt, and both were central to the economic idolatry that sustained the nation as a whole….

The corruption occurs because

to ensure “unblemished” animals, you were required to purchase your animals at the gate of the temple where the prices were higher than the country-side. And, as with any regressive tax or price system, the costs tended to be felt more by the poor than the wealthy. To purchase one pair of doves at the temple was the equivalent of two days’ wages. But the doves had to be inspected for quality control just inside the temple, and if your recently purchased unblemished animals were found to be in fact blemished, then you had to buy two more doves for the equivalent of 40 days’ wages!

Josephus, the Jewish historian, tells a story of Rabbi Shimon ben Gamaliel (son of Gamaliel, Paul’s personal spiritual trainer), who went on a campaign against price gouging. But unfortunately stories of someone trying to protect the poor from the practice are rare. More common was the reference in the Jewish Mishna that the costs of birds rose so fast in Jesus’ time that women began lying or aborting their babies to avoid the required and punitive fees…

The result was that for a poor person, the Money Changer’s share of the temple tax was about one day’s wages and his share of the transaction from international to local currency was about a half-day’s wages. And that was before they purchased their unblemished animals for sacrifice and then had to buy them again (at an enhanced price) because the inspector found a blemish or [something else that made them] inadequate for the offering… [I urge you to read the entire article.]

There is something horribly contemporary about this scene, and soon, Stan pulls us directly into today. I notice that what he is talking about is often called, in my part of the church, social justice. And it is contrasted with evangelism, which is sometimes touted as a proper telling of the good news. But the spiritual— the euangelion— does not exist without the concrete; to be specific, evangelism without social justice is a lie. It is an idolatry which seeks to have the benefits of God along with all the ill-gotten gains of the oppressors. It is not cheap grace, it is theft. Stan says

Those who today believe the current global economic system has failed, often fall into three types. First, those who believe that the system itself is wrong (the very fact of markets creates wealth and poverty, and that’s wrong); second, that this particular model of economic globalization is wrong (other systems could be designed to be more fair, but this one is not); and finally, that the system is fine, but there are abusers of it and discontinuities within it (if we could just get markets to work right then eventually all boats will be lifted). Jesus seemed to be in at least the second camp, and maybe even the first: the very existence of the market at all was what caused evil. According to what we know of him in this text itself, he would most likely be against the marketization of life itself.

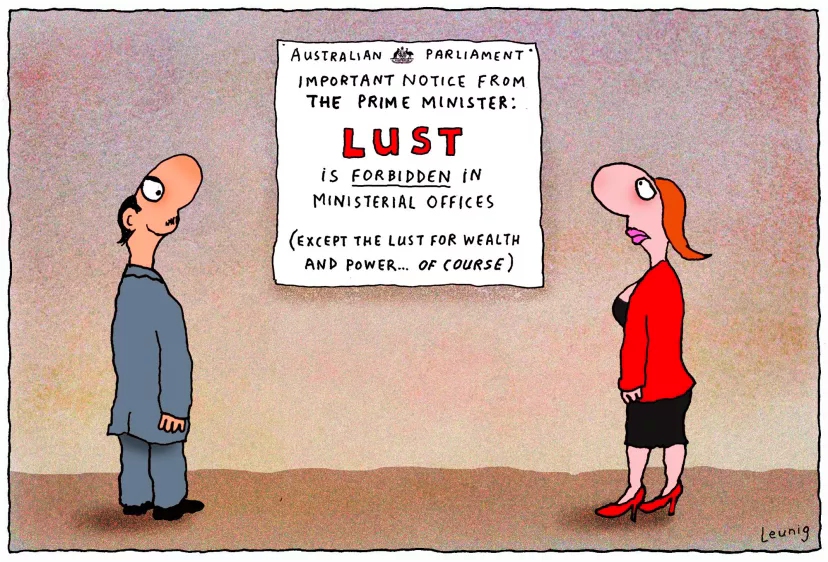

The marketization of life itself: Our culture revolves around economics. Everything is about money; the getting of money, the spending of money, the fear of not having enough money. Everything has a value; everyone has a price. The great sin of our culture, the only sin which really matters is if we challenge the money system. In the brouhaha over Barnaby Joyce a Leunig cartoon says it all: "LUST is forbidden in ministerial offices. (Except the lust for wealth and power… of course.) A different economic system is beyond our imagining; we scorn such ideas as utopian and ridiculous, but really, we do not know how else to live. This inability to imagine is a sign of our enslavement to mammon. (Image courtesy of Michael Leunig)

The marketization of life itself: Our culture revolves around economics. Everything is about money; the getting of money, the spending of money, the fear of not having enough money. Everything has a value; everyone has a price. The great sin of our culture, the only sin which really matters is if we challenge the money system. In the brouhaha over Barnaby Joyce a Leunig cartoon says it all: "LUST is forbidden in ministerial offices. (Except the lust for wealth and power… of course.) A different economic system is beyond our imagining; we scorn such ideas as utopian and ridiculous, but really, we do not know how else to live. This inability to imagine is a sign of our enslavement to mammon. (Image courtesy of Michael Leunig)

Jesus is at the centre of all this. Mark D. Davis sums up the problem of "the Jews" of John's gospel admirably:

Richard Horsley (Hearing the Whole Story) argues that when Mark uses the word Ἰουδαίοὶ, we should translate it “Judeans,” and not “Jews.” … Horsley’s point is that Mark makes a strong distinction between Galilean and Judean ways of being faithful. I don’t know if John has that same kind of distinction in mind, but I … believe it reflects the inner struggle for the soul of Jewish piety better than the anti-Semitic assumptions that often shape Christian interpretations.

The inner struggle for the soul of Jewish piety: Where is the inner struggle for the soul of Christian piety? In other words, the text is not about Christianity as superior to the Jewish temple system. It is about the locus of God within Christianity or Judaism. Where is God? And the answer of John is: in Jesus.

Part of the reason I can never quite fit in, I suspect, apart from the scars of my trauma, is that Jesus constantly criticises the church. We are in a constant, years long panic about the church, in my denomination: how will it survive, how will we keep the church going, what must we do for growth? As with the economics of the wider community, I sense I am in the presence of something profoundly wrong, and yet for which I can imagine no alternative. How do we be church and yet die? (Was not that also the issue in Mark 8:26-38, last week?)

I am not saying that there is something fundamentally wrong with our doing of church here in South Australia, but that I have the answer. I am saying that if God is found in Jesus, then however we do church, we will never fit in, because he keeps clearing out the idolatry, and keeps turning over our closed tables. If we are happy with church, there will be a visitation which will upset us.

And part of my struggle to find energy to do the tasks of everyday living, as my culture understands them, is that Jesus calls our everyday culture idolatry. If we are Christian, we should find ourselves profoundly out of step with the way people live. (And called to live with them, anyway.) But there should be deep cognitive dissonance present within our lives.

Jesus lived in this. Luke 22:44 says "In his anguish he prayed more earnestly, and his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down on the ground." It costs us to live apart from the mainstream. Paul calls it a foolishness.

the message about the cross is foolishness… we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling-block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God… ( from 1 Corinthians 1:18. 23-3)

The cross calls us to walk uphill, to live against the tide. To think it will not cost us, is itself foolishness. And those who preach only glory, and who gloss over the cost, and the emotional, mental cost, have a certain blindness.

Have we left the world to join a church, or are we seeking to leave the world and follow Jesus? There is always a difference.

Andrew Prior

Direct Biblical quotations in this page are taken from The New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Please note that references to Wikipedia and other websites are intended to provide extra information for folk who don't have easy access to commentaries or a library. Wikipedia is never more than an introductory tool, and certainly not the last word in matters biblical!

Key Articles

Karoline Lewis: Commentary on John 2:13-22

Stan Duncan: Jesus and the International Currency Traders in the Temple

Also on One Man's Web

John 2:13-25 - A banal turning over of tables

And about the title: The Affect of Jesus is deliberate.